Integrating Design Thinking in Product Design and Data Analytics

The Impact of My Third Culture Upbringing on Perspective, Empathy and Understanding

Growing up as a third culture kid deeply shaped how I perceive people, language, and society. In places where I spoke one of my three languages, I became acutely aware of how differently cultures behave and make decisions. Moving from that diverse background to school in America, particularly in the melting pot of New York City, highlighted the vast mix of values, beliefs, and traditions among my peers.

These contrasts sparked curiosity while growing up, and led to conversations with friends from various backgrounds about philosophy, culture, and identity. Over time, I began to understand how mindsets, habits, and education influence our worldviews. Even within the same environment, people interpreted experiences differently based on language, culture, and societal context.

This realization of how societal, cultural, environmental, and educational factors shape individuals helped me see how early habits continue to influence how we think and make decisions. My interactions with people from all walks of life helped me understand how these factors intertwine to shape the way we live and interact. What began as observation evolved into a personal narrative, helping me appreciate the nuanced interplay of forces behind human behavior.

Teun den Dekker (2021) expresses this well, describing design thinking as “a different way of looking at the world, to see the possibilities in the impossible, to make connections that were not thought of before, and to work in interdisciplinary teams that challenge everyone to seek solutions for a problem.”

Bridging Systems Thinking and Design Philosophy

During my undergraduate studies in philosophy and psychology, I discovered I had been engaging in systems thinking all along, intuitively solving problems in a structured, holistic way. This method later connected directly to product design, especially once I was introduced to the principles of design thinking during my graduate level coursework. Without realizing it, I had been applying those principles in daily life, and in doing so, deepened my understanding of human behavior.

Growing up with limited resources, I had to be intentional with every decision I made, as each one affected my time, money, and energy. I learned to think logically, weigh outcomes, and plan ahead. This kind of thinking, much like a decision tree, mirrors how designers and adjacent professionals evaluate options, mitigate risks, and strategize solutions.

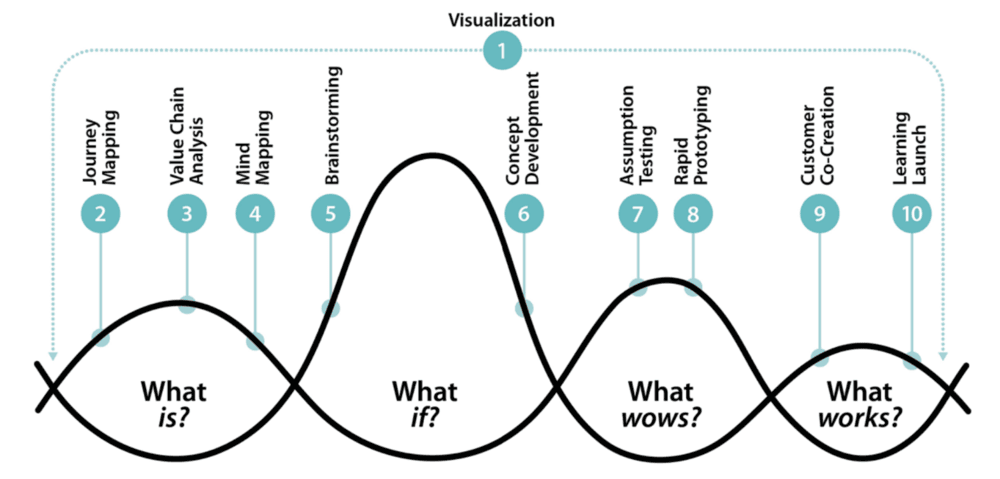

In a video lecture called What is design thinking?, Liedtka effortlessly sums up design thinking as something “more than just thinking; it involves a systematic series of questions”, (Liedtka, 2016). She continues on with the video, emphasizing how anyone can use design thinking principles in their life. She emphasizes that one must start with the “present, understanding current reality, and then broadening the definition of problems or opportunities”. Liedtka notes that attention to the present helps uncover unarticulated needs, which is crucial for generating innovative design criteria. In a professional setting, this is the creative way to iterate on a solution that will solve a problem for a user or a demographic.

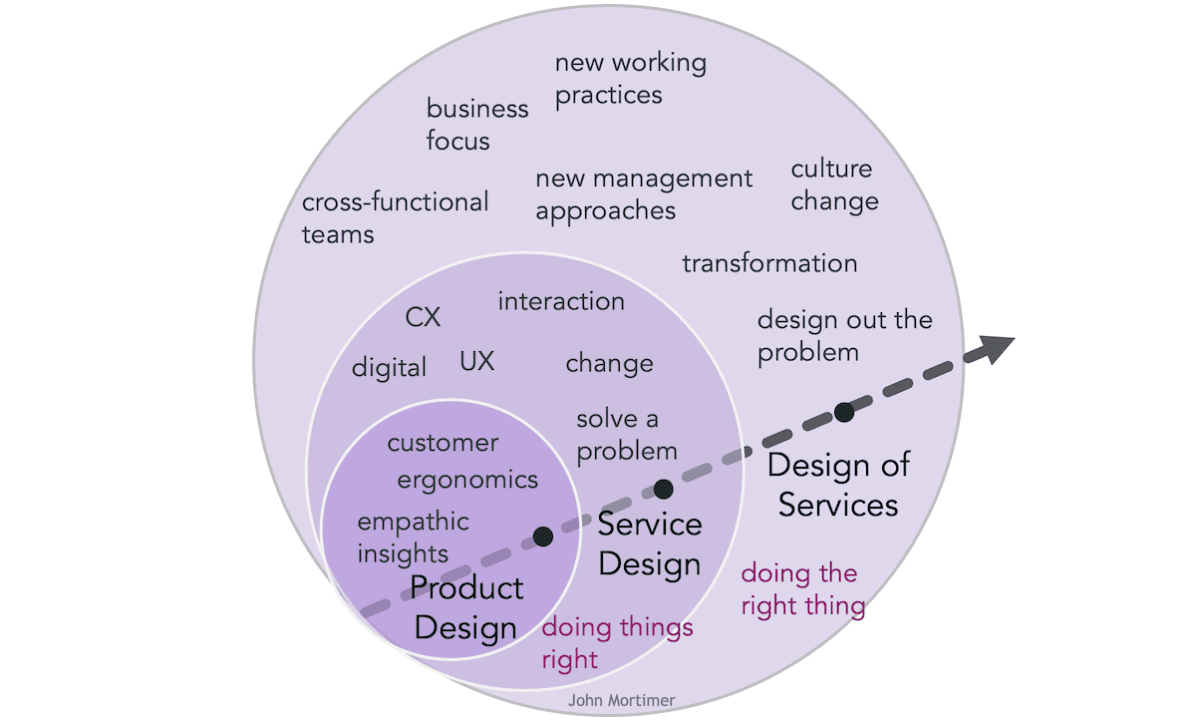

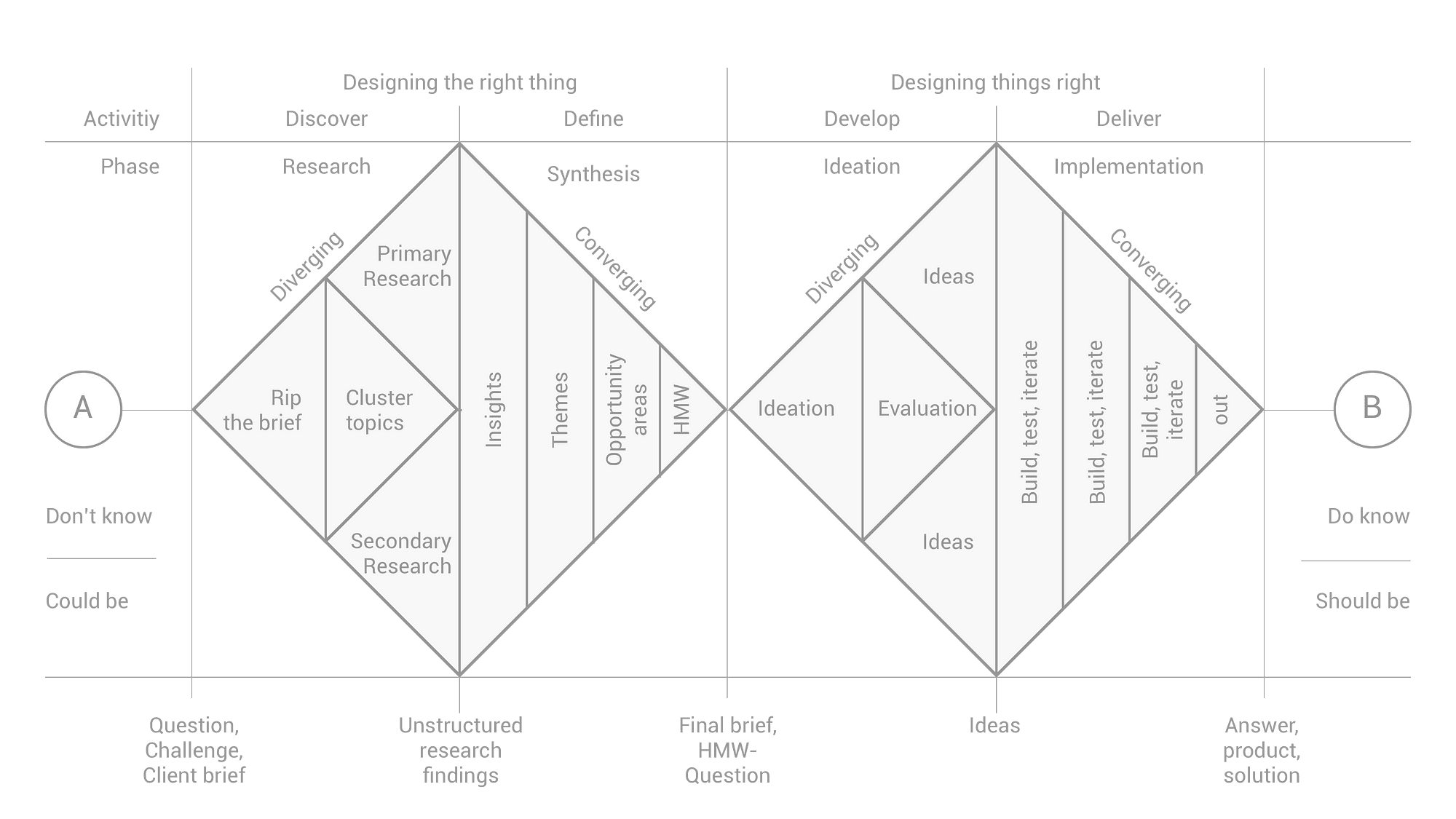

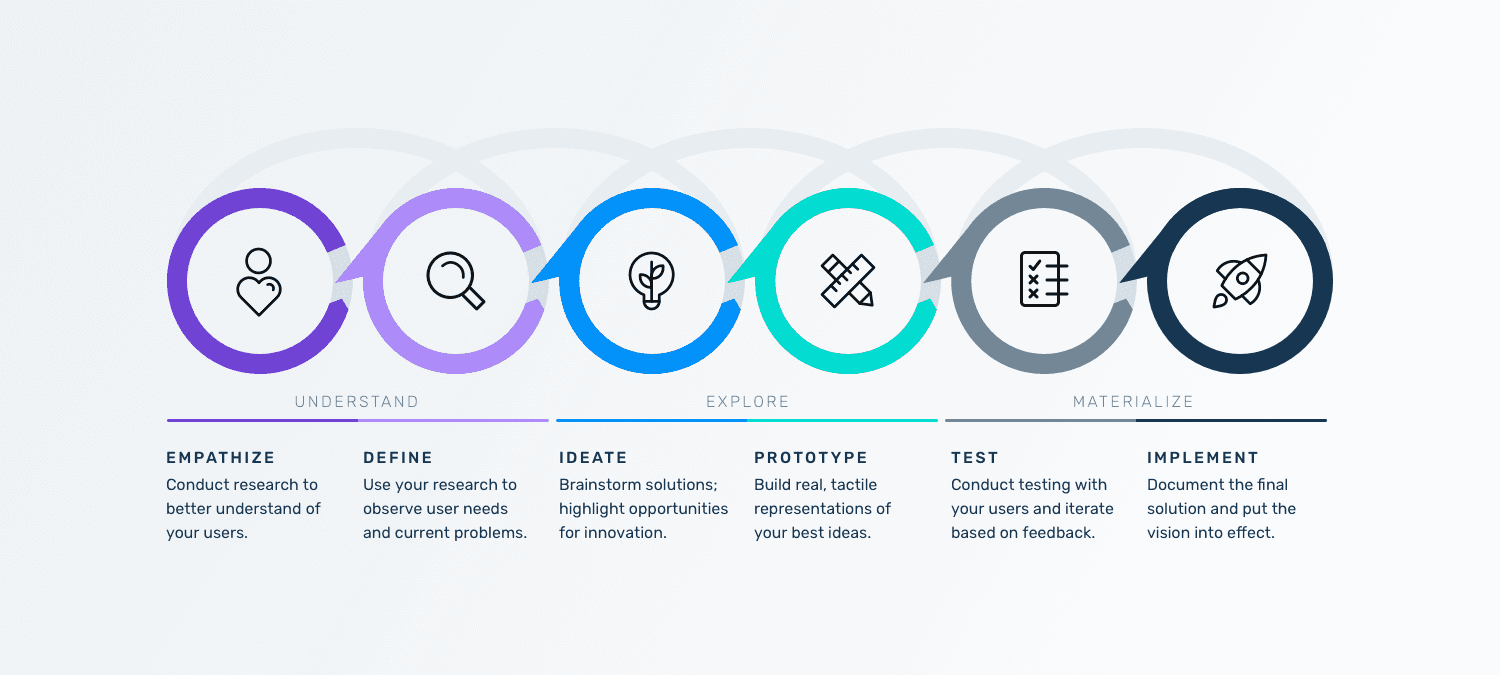

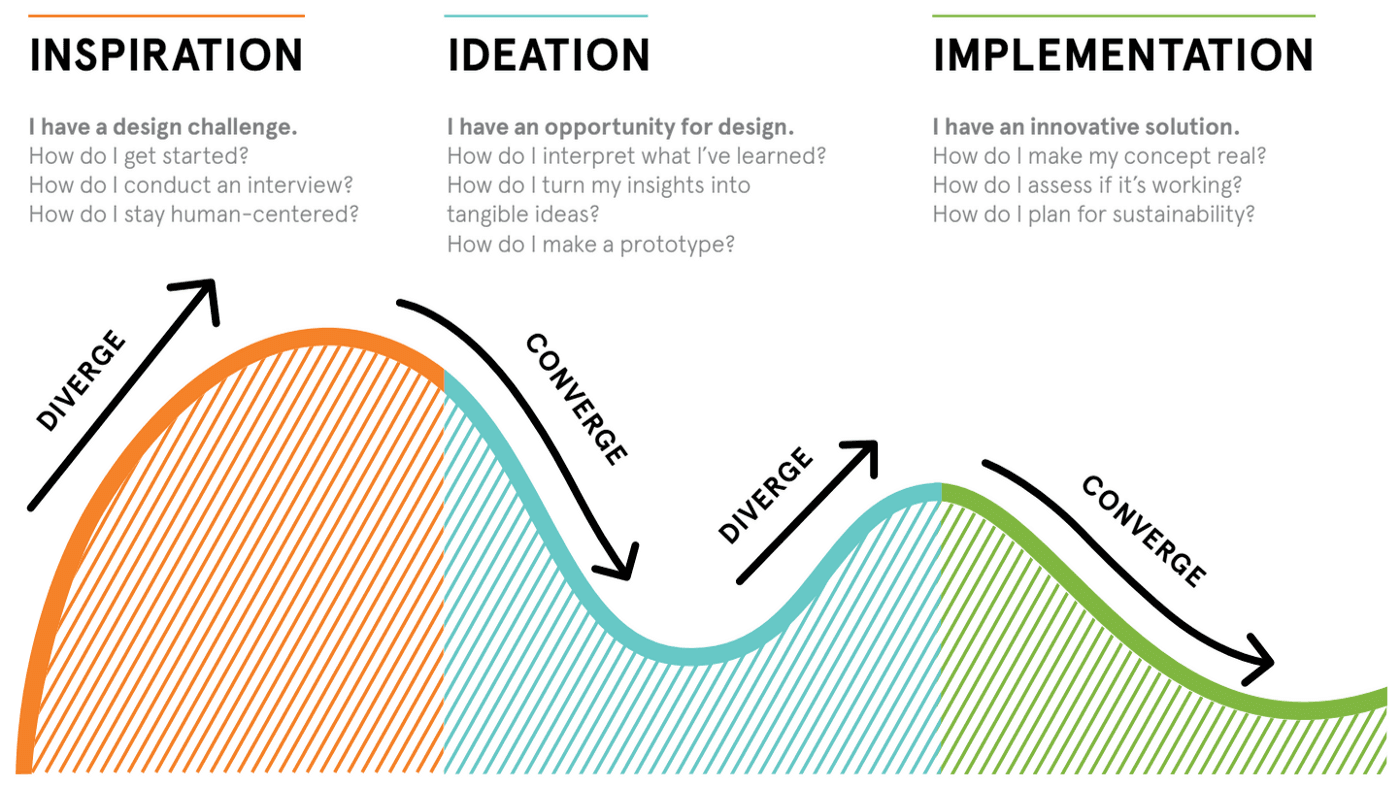

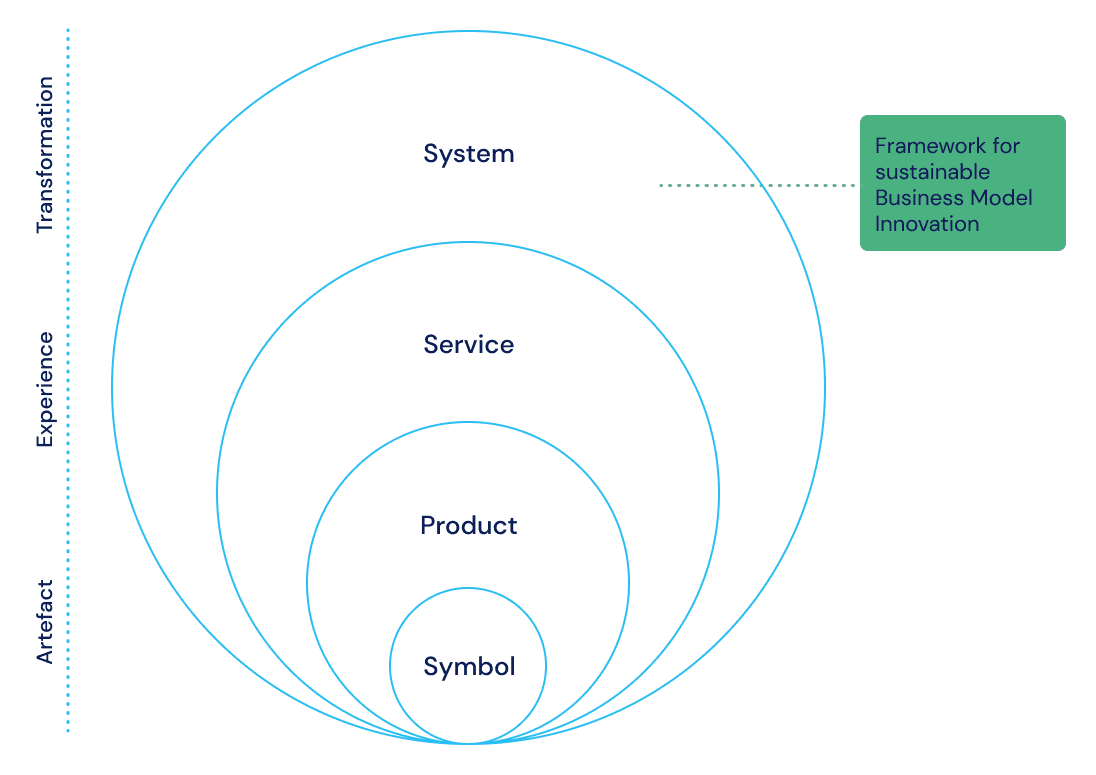

In design thinking, there are processes used with their own unique approach and stages. Three of the popular frameworks that different professionals use are the Double Diamond Model, the Stanford Design Thinking Process, and IDEO’s 3 I’s.

There are several design thinking frameworks used across disciplines.Some commonly cited frameworks are:

Double Diamond Model – Consists of Discover, Define, Develop (Ideate), and Deliver, highlighting phases of divergence and convergence.

Stanford Design Thinking Process – Includes Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test, with a focus on user needs and iterative development.

IDEO’s 3 Is – Inspiration, Ideation, and Implementation, capturing the process from gathering ideas to testing them.

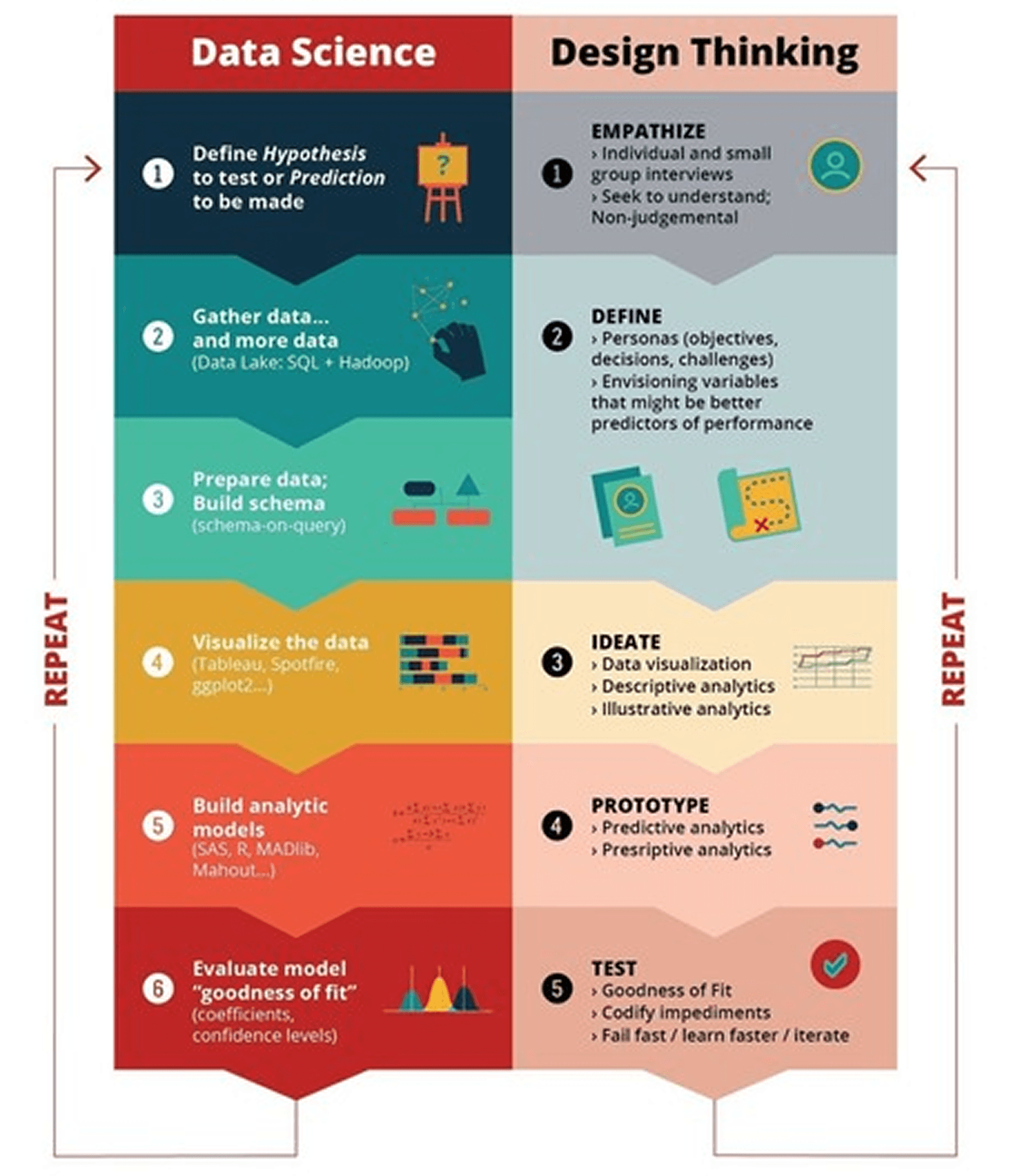

Leidka mentions a "what if" stage, and how that is all about coming up with different ideas based on what we've learned from gathering information. In creating products, it happens when exploring and defining. In the data world, it occurs during preparation and processing. Design thinking is a holistic principle during brainstorming, to continue asking interesting questions to spark creative ideas. For product designers and data professionals, after gathering and sorting info, there comes a point where they figure out a way to roadmap to solve the problem, making sure it fits what stakeholders need and what the organization can do.

Many times, product designers and data analysts work together, sharing data, information, and ideas with each other. They're often on adjacent teams, working within a larger team to problem solve. Both disciplines utilize similar methods, the only difference is the software and tools they're using to reach their goal.

Ideas that pass this test become potential candidates for testing with real users in the next phase, called "what works." In this phase, there's testing done on different versions of ideas with users, making improvements until product and data professionals are confident in the new concept.

Liedtka's idea that design thinking begins by understanding the present and expanding problem definitions fits with the big-picture thinking in systems principles. The evolution of design thinking in business, focusing on user needs and challenging biases, shows up in the practices of forward-thinking companies. Design thinking quietly tackles human biases, encouraging creativity and a break from the norm.

Purdy, E. R.(2023), sums up design thinking similarly – understand clients' needs, use prototypes for exploration, and embrace experimentation, even if things go south. Teun den Dekker's six key attitudes for successful design thinking – “flexible thinking, integral work, empathy, cooperation, imagination, and experimentation” – as outlined by den Dekker (2021), is another great framework to the guiding principles for product design. Product designers, like design thinkers, use these attitudes to create user-friendly and innovative solutions, focusing on empathy, collaboration, and creative ideas. Experimentation, crucial for refining designs, completes the cycle.

Combining systematic thinking, design philosophy, and design thinking principles is similar to telling a story of teamwork and innovation. This connection acts as a bridge between my background and the exciting fields of product design and data analytics.

Bridging Design Thinking with Product Design in Data Analytics

The surge in data analytics, and technology in general nowadays has caught everyone's attention. We may have heard about statistical thinking, but there's another way of approaching data through design thinking. When a data analyst tackles a problem, there's a whole range of ways they can go about it—like how they build, create, and design their analysis, including the tools and methods they use. These choices affect not just the analysis itself but also how the person using it experiences it.

As mentioned in D’Agostino McGowan and team (2022), the design principles, “drawing inspiration from both statistical thinking and design thinking, serve as a set of characteristics that guide the construction of a data analysis”. They encompass various elements such as code, data visualization, narrative text, and statistical models, allowing a data analyst to craft an analysis that is not only accurate but also tailored to the specific context and purpose.

Throughout the text, the authors talk about the design thinking perspective that facilitates a clear separation between producers and consumers, aligning priorities based on structured principles. The journal introduces a set of data analytic design principles with the goal of describing variation between data analyses, and they describe these principles as “Data Matching”, “Exhaustive”, and “Skeptical”.

Data Matching ensures that available data aligns with specific question requirements, influencing analysis methods. It recognizes variations in question specificity, impacting potential data considerations. Exhaustive promotes a thorough exploration of a question using diverse methods, revealing different data aspects for a comprehensive understanding. Skeptical encourages considering multiple, related questions with the same dataset, fostering a nuanced analysis. It reflects a critical and open-minded approach, acknowledging the complexity of phenomena beyond a single question.

The scientists in that journal brought in those design principles as a set of design guidelines for their data analysis. They aim to describe the variation between different data analyses and emphasize the role of these principles in the application of design thinking to the practice of data analysis, specifically for the datasets they had for the case studies they were referencing.

Similarly, various aesthetic principles, such as UX laws, find application in the design of data visualizations. These shared principles encompass aspects like order, color, accessibility, and inclusivity. Whether crafting interfaces, visualizations, or other visual elements, the goal remains consistent—to weave a narrative, seamlessly integrate with a product, and deliver meaningful information to the user.

In the interconnectedness of data analytics and product design, both play the role of storytellers. Data analysis provides insights and guides decisions through statistics and data, while product design creates user-friendly experiences centered on empathy. Despite their differences, both fields share a commitment to users, thorough research, data analysis, empathy, inclusivity and storytelling. Together, they craft experiences that inform decisions and resonate with users, weaving stories into the products they create.

Overcoming Challenges and Understanding Limitations

Innovation in a professional setting comes with challenges; seeking superior solutions, cost reduction, and employee support. Traditional approaches often struggle with creativity constraints, budget, and user criteria inclusion. By encouraging focused inquiries, “design thinking promotes the emergence of a limited but diverse set of potential new solutions” (Liedtka 2023). Design thinking steps in as a structured solution with a holistic approach to problem solving. It guides teams through customer discovery, idea generation, and testing experiences, addressing biases. Design thinking immerses innovators in user experiences, organizes data, builds team alignment, encourages fresh ideas, and gets user feedback.

While recognizing its advantages, it's crucial to be aware of its limitations. Moving forward, there's a focus on refining applications and overcoming challenges. Operating as a social technology, design thinking not only influences innovation but also revolutionizes experiences, promoting engagement, dialogue, and ongoing learning. As technology advances, there will be more tools available to get tasks done quicker with less time and more accuracy, but the holistic process that guides those solutions will always remain the same.

In general, design thinking is a great philosophy to implement in many areas of one's life. Effective communication and storytelling are vital in both data analytics and product design when using design thinking. This approach puts a spotlight on inclusivity and accessibility, making sure that complex information is presented in a way that helps users understand and make informed choices. Design thinking embodies a collaborative and inventive narrative, weaving together product design and data analytics, paving the way for a future where these domains seamlessly integrate.

References

Liedtka, J. (Ed.). (2016). Design thinking. University of Virginia Darden

Purdy, E. R., PhD, & Popan, E. M. (2023). Design thinking. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

Admin, I. U. (2022, August 30). What is design thinking? https://www.ideou.com/blogs/inspiration/what-is-design-thinking

Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. W3C. (n.d.). https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/

Dekker, T. den, & Maarsman, R. (2021). Design thinking. Noordhoff.

Garcia, PhD, R., & Dacko, PhD, S. (2015). Design thinking for sustainability. Design Thinking, 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119154273.ch25

Dam, R. F. and Teo, Y. S. (2022, June 27). What is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular?. Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/what-is-design-thinking-and-why-is-it-so-popular

Liedtka, J. (2023). Design thinking in organization design. Designing Adaptive Organizations, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108762441.002

Yablonski, J. (n.d.). Laws of UX. https://lawsofux.com/

Luchs, M. G. (2015). A brief introduction to design thinking. Design Thinking, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119154273.ch1

McGowan, L. D., Peng, R. D., & Hicks, S. C. (2022). Design principles for data analysis. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 32(2), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2022.2104290

Szudejko, M. (2023, October 7). How to use color in data visualizations. Medium. https://medium.com/towards-data-science/how-to-use-color-in-data-visualizations-37b9752b182d

Monge, C. (2023, August 2). Disability & Design: Building Digital Products for UX accessibility. Blank Factor. https://blankfactor.com/insights/blog/disabilities-and-ux-accessibility/

Royalty, A., & Roth, B. (2016). Developing design thinking metrics as a driver of creative innovation. Understanding Innovation, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19641-1_12

Liedtka, J. Why design thinking works. Harvard Business Review. (2023, June 14). https://hbr.org/2018/09/why-design-thinking-works

©2025